Kids Are Tiny Scientists When It Comes to Debunking Santa

A Bayesian journey from magic to logic

I strongly believe in gravity.

When I see an object seemingly defying gravity, I look for the hidden wire, magnet, or trick that prevents it from dropping. Seeing a video of a flying man doesn’t make me doubt gravity. I know the video must be fake. It would take something insanely extraordinary for me to lighten my solid belief.

Others, who are already in deep skepticism, have a completely different takeaway from such a video. They welcome evidence to support their doubt and move towards a stronger skepticism quite easily.

In my experience, small kids have a similar belief in Santa as I do in gravity. They wholeheartedly believe it to be true, almost without a doubt. So when they come across any evidence that could shake their belief, they look away. Or come up with an explanation on their own that justifies what they experienced in the world where Santa is a given.

I remember the time that came after the unshakeable belief. I didn’t look away anymore. When a classmate told me that her parents bought her Christmas presents, I listened. I became receptive to the discrepancies in the story. It started to bother me that we stored the neighbor kid’s present until Christmas, even though I hadn’t blinked an eye in previous years. And that the Santa visiting us at home bore a striking resemblance to my dad’s friend.

Still, there were experiences that increased my trust. Like when the suspicious Santa at a Christmas party pulled out my drawing that I gave to a different-looking one at home the previous day. As confusing as it was, the drawing showing up if there was no Santa made little sense to me. So I believed a little more.

When the doubt crept in, I even started to actively test the existence of Santa. I set up traps to catch him in the middle of the night. I also tried to catch my parents in a lie.

When I was almost ready to commit to disbelief, I set up a fundamental test to decide once and for all, which ended up backfiring on me. I asked Santa to bring me a real cat. My parents were against getting a cat; meanwhile, I believed that if Santa existed, he would bring me one. And to my ultimate surprise, he did. Unbeknownst to me, my Mom had discovered my secret stash of cat food. To prevent a childhood trauma, she abandoned the plush toy idea and found me a real kitten the very night before. So there I was, back in doubt again.

I don’t remember any more major milestones in my discovery journey; I just slowly became a non-believer after a series of small events that put cracks into the story of Santa.

Reminiscing about my journey of debunking Santa, and reading a fascinating paper about a related study1 , I realized that the process has a striking resemblance to one well-known to science: a Bayesian inference.

Hypothesis testing is a fundamental part of applied mathematics, the mathematics that supports our everyday lives. Scientists use it in all fields of research: clinical testing for drugs or medical treatments, physics to test their theories, and quality testing in factories. The list is truly endless.

Santa either exists or he doesn’t.

The existence of Santa is the null hypothesis (ℋ₀), and kids are tiny scientists trying to prove either that he does exist (meaning that ℋ₀ is true) or that he does not (meaning that ℋ₀ is false). Either conclusion requires a solid argument. (You don’t want to be wrong about Santa!) So, kids have their work cut out for them.

Also, belief is not zero or one; it is a scale. A probability, a number between zero and one. One is perfect belief, zero is total disbelief.

In my experience, small kids have a very strong belief accompanied only by a tiny bit of doubt, since that’s what they are encouraged to do by the most trustworthy people: their parents. This initial belief is what science calls a priori estimate. Here, it is a big weight in the “believe” corner, leaving only a tiny weight for doubt.

But kids’ belief in Santa isn’t static.

Because new evidence comes once in a while. Santa grants them their deepest wish, or Santa messes up and forgets to eat the cookies and milk left out for him. If the former happens, the kids’ belief increases. If the latter, it decreases. By how much? That depends on the “gravity” of the evidence.

If Santa doesn’t eat the cookies, it’s a small issue. Easy to come up with an excuse; only a slight decrease in belief. If Mom is caught wrapping the presents, that’s a big one. A big drop for the belief-meter.

There is another important factor that goes into the updating of said belief-meter: those already in doubt are more sensitive to Santa’s screw-ups. Others with a solid belief are not. All in all, the same event has a different effect on kids with different a priori beliefs.

Let’s look at how the update happens. You'll see it naturally follows the two properties we've discussed. Here comes the math.

We are seeking the probability of Santa’s existence (ℋ₀) given the evidence (E) that we have. This is called a conditional probability, and it’s written as P(ℋ₀ ∣ E). This is the big question that we don’t have an answer to right away, but we have a better idea about the other direction: what the chance of this evidence is if Santa exists (or doesn’t).

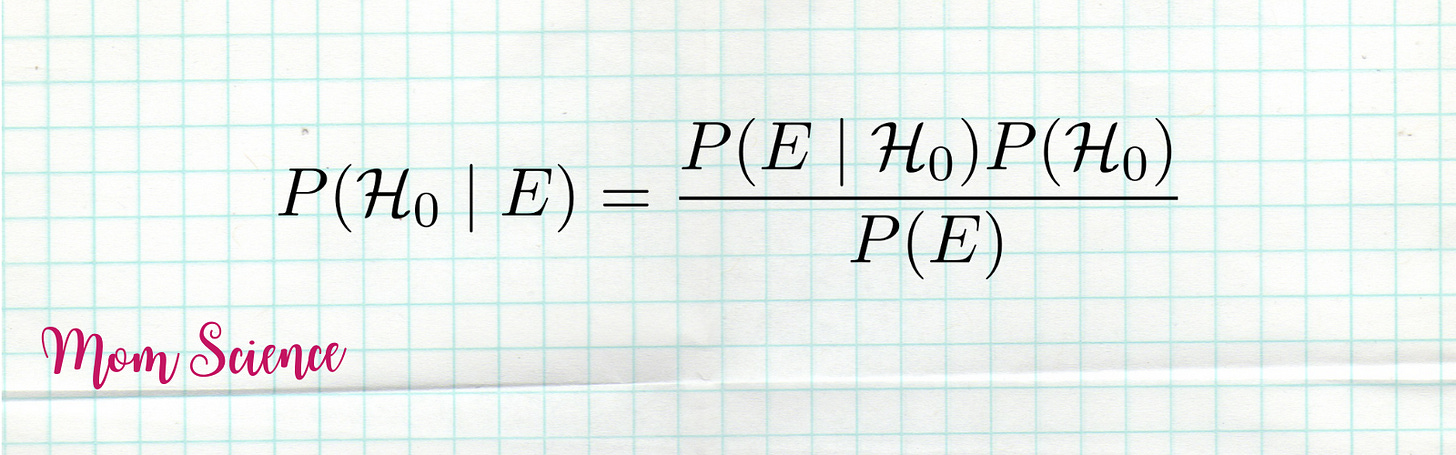

Using Bayes’ Theorem, we are able to switch the evidence with the null hypothesis:

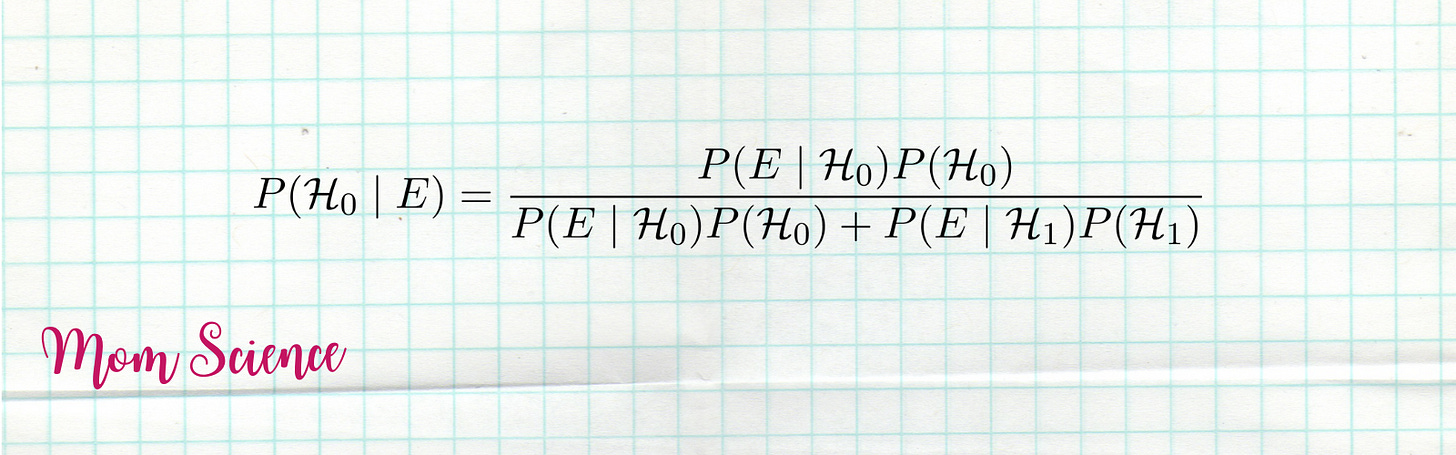

One more step: the law of total probability, to expand the probability of the new evidence. Think of this as the “Reality Check”: looking at all the ways an event could happen, whether Santa is involved or not. Here we will need a name for what happens if Santa doesn’t exist — we’ll call this the alternative hypothesis (ℋ₁). Then, the law of total probability results

Believe it or not, we have arrived at our formula for the belief inference. Why?

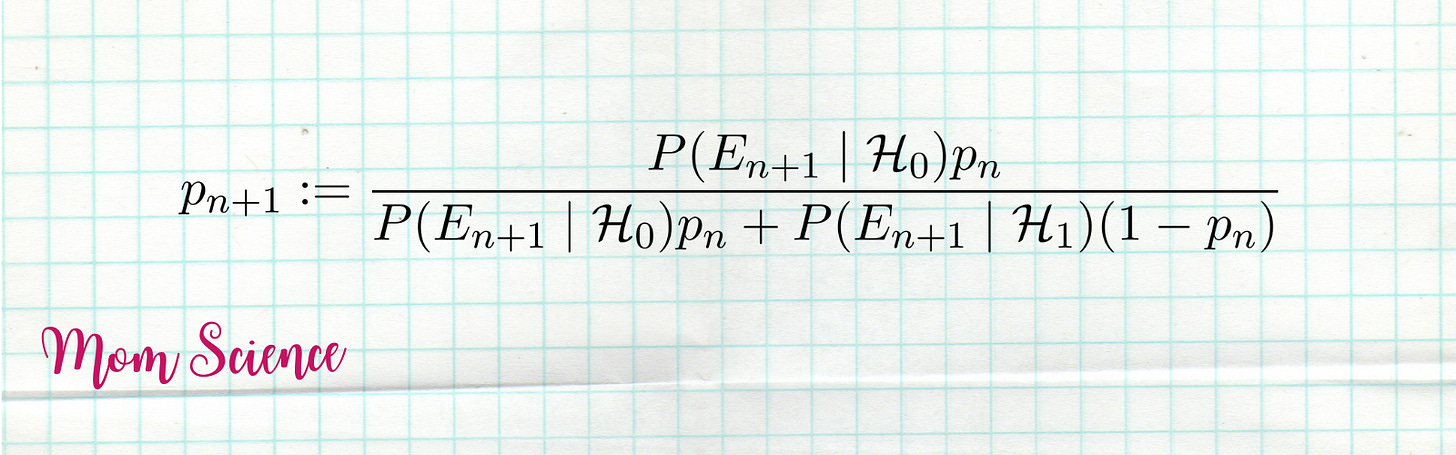

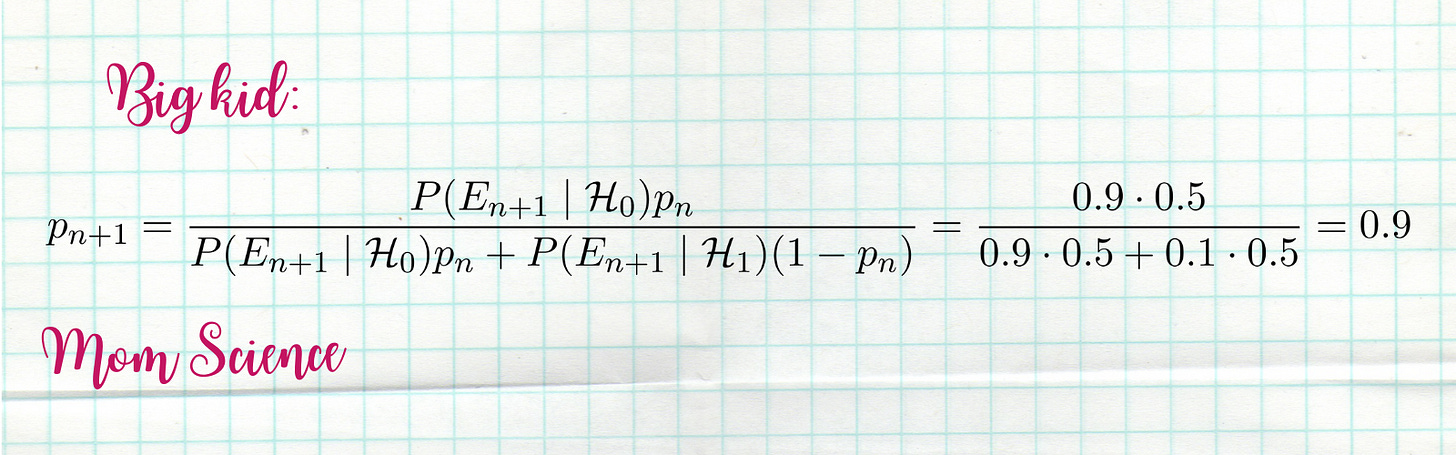

Let’s say we receive new evidence: Eₙ₊₁. It means that we have already had evidence E₁, ..., Eₙ, and there already is a guess for the chance of Santa being real based on these. Call it pₙ. This will be our a priori guess in this round of the inference process. All we need is to adjust it using the brand new information Eₙ₊₁. How do we do that? We use the formula we just derived, estimate the probability of the null and alternative hypotheses with our best guess so far, pₙ and 1-pₙ, and define the new estimate as

This means that we adjust our belief to the probability that Santa exists given this new evidence.

We’ll now use Bayesian inference to update our belief in Santa. Let’s see if it really works as expected!

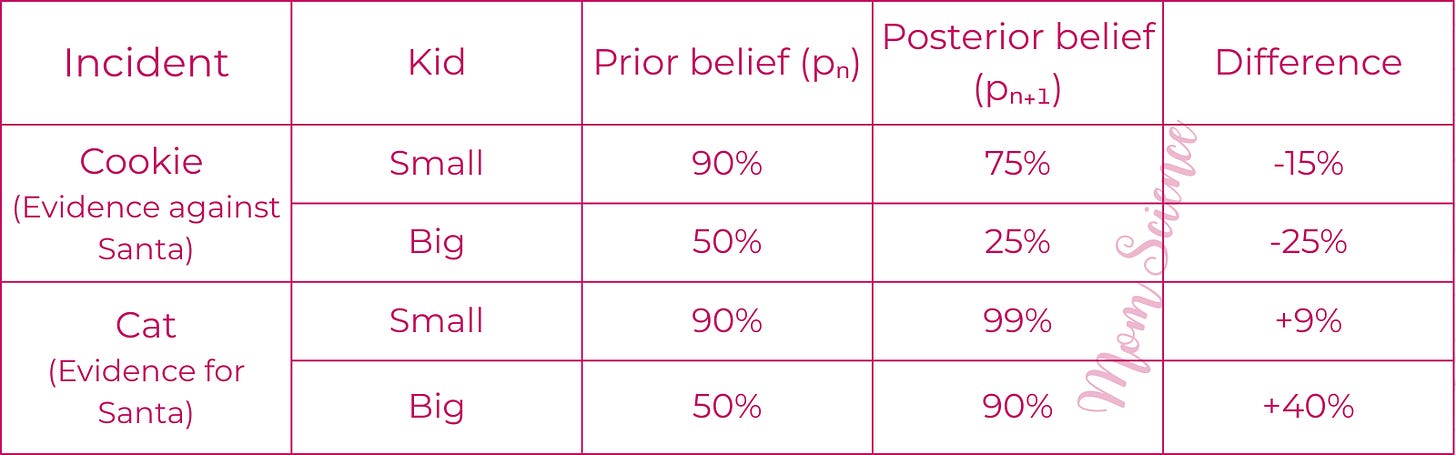

Consider two siblings who prepare cookies and milk on a tray for Santa and leave it hidden in the chimney. Yet, in the morning, they find the delicacies untouched. What a bummer!

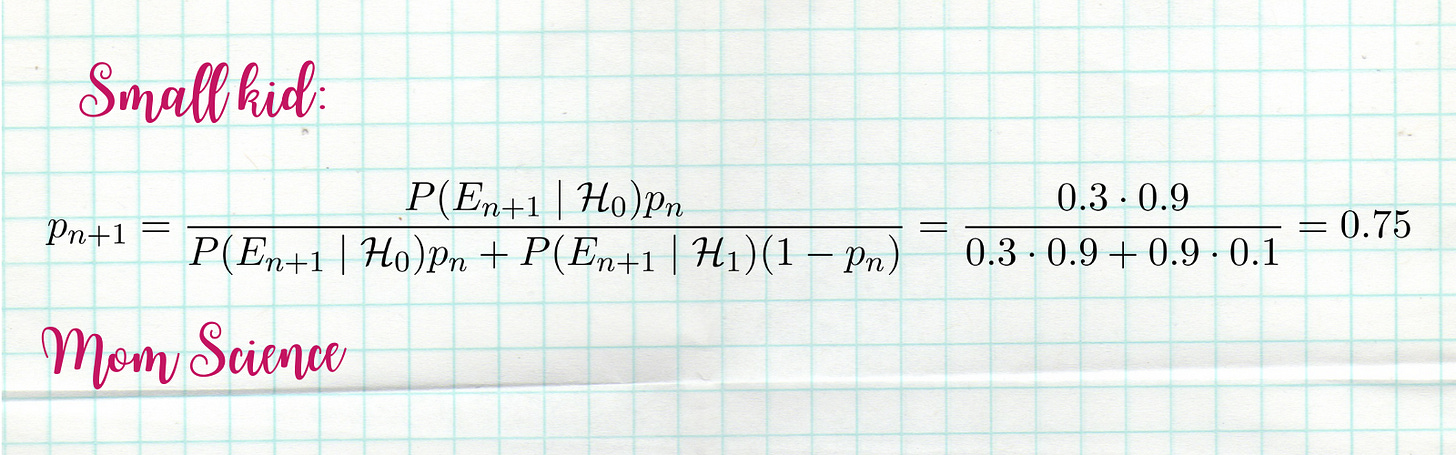

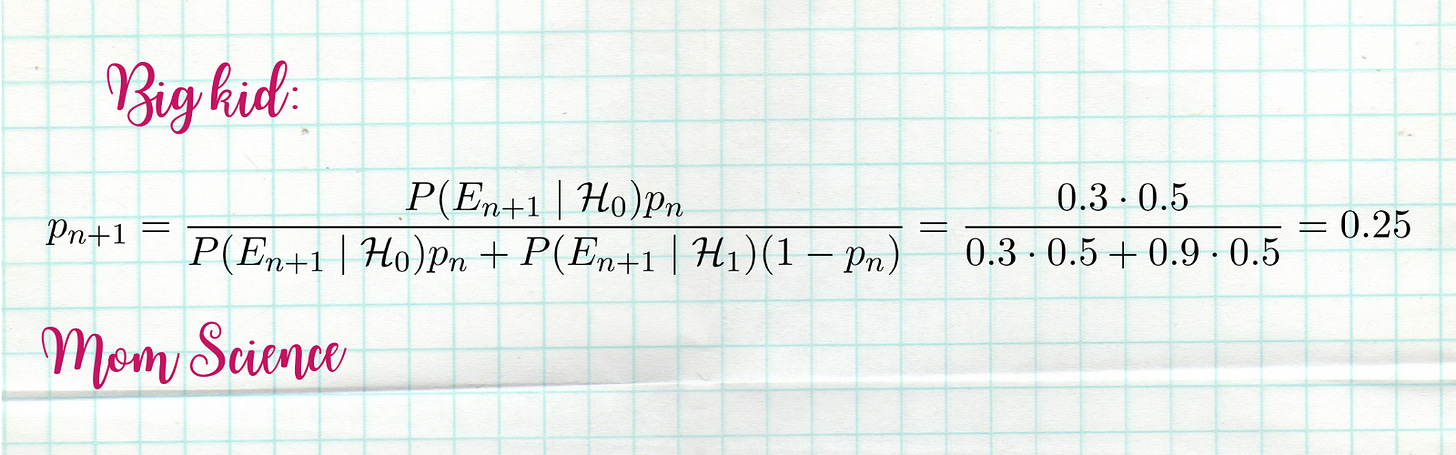

The small kid still had a very strong belief in Santa before this incident; let’s say he was 90% sure that this beloved mythical creature exists. The older kid was already in doubt; he suspects that their parents are behind the gifts he gets. He was right in the middle, giving a 50% chance that Santa is real.

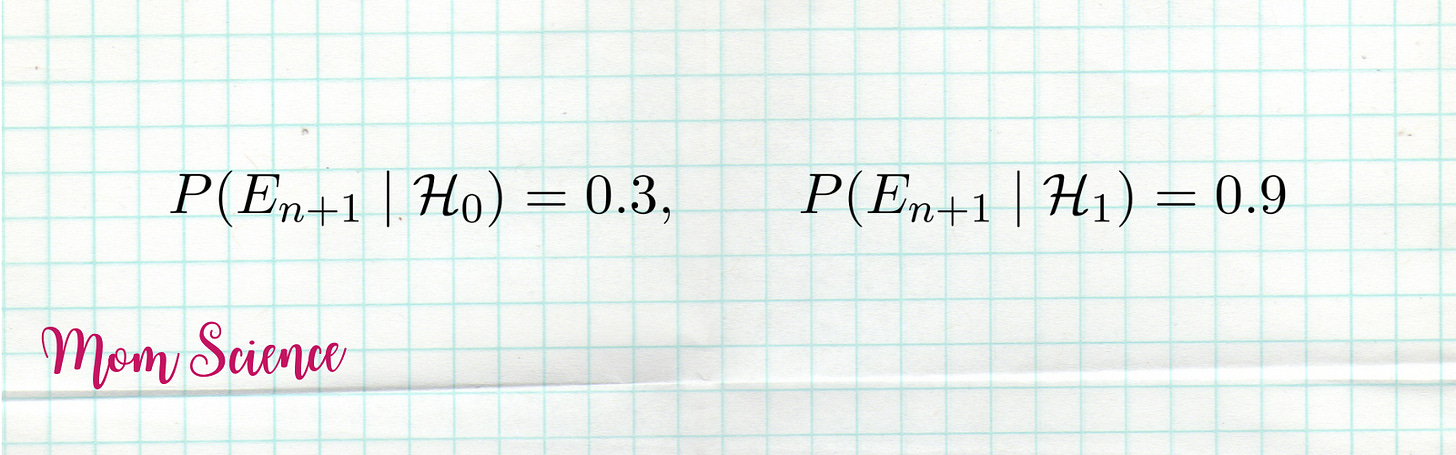

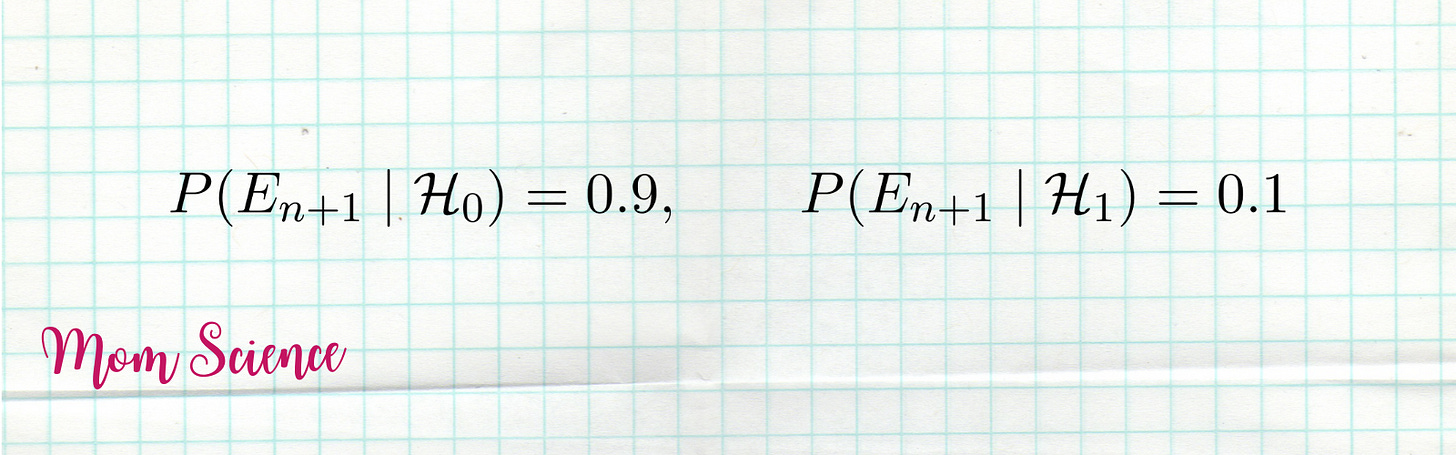

We have to put numbers behind the witnessed incident. The parents suggest that Santa probably wasn’t hungry last night, which is why he left the tray untouched. Not a great explanation, nor a terrible one. We’ll say that the chance of the tray staying untouched, given Santa does exist, is only 30%.

Meanwhile, if it is the parents who act in place of Santa (who obviously don’t come down the chimney), it is likely that they didn’t find the cookies and milk. Give it 90% that the tray is untouched if Santa doesn’t exist.

What does this mean for the kids? The small kid’s belief drops from 90% to 75%. A 15% decrease.

Meanwhile, the big kid now only believes with 25% probability instead of the previous 50%. A 25% drop.

As we see, with Santa’s mistake, both belief-meters dropped. However, the decrease was bigger for the kid who already doubted, and smaller for the firm believer.

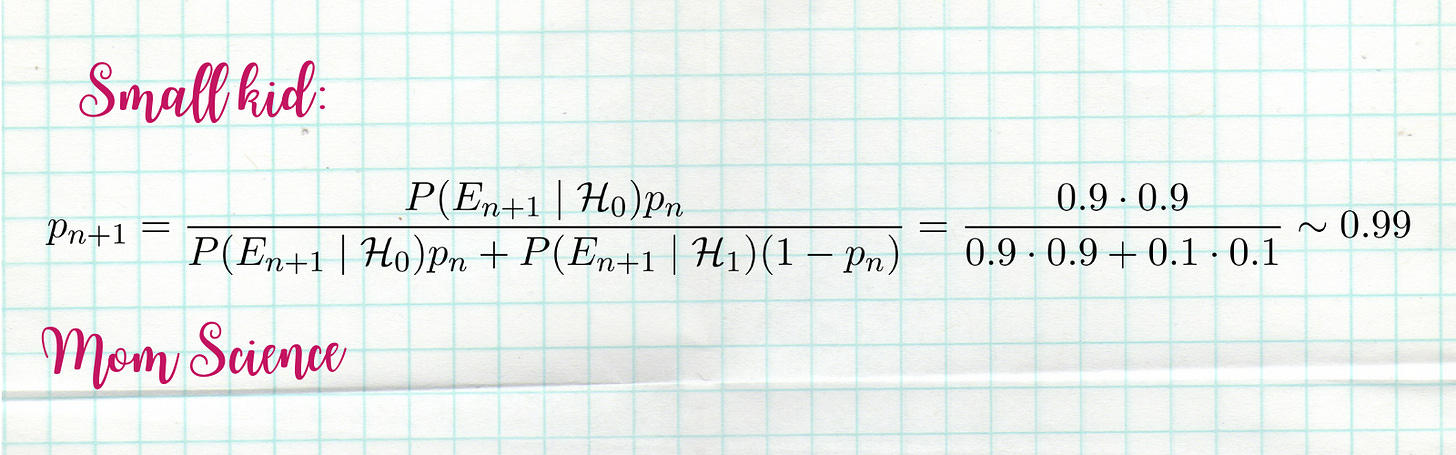

Remember my story with the cat? Let’s see what that results. If the kids from the previous example ask for a cat that their parents are strongly against, and they get the coveted gift, that should be a significant win for Santa. He has no reason to fail to deliver the request: getting a cat shouldn’t be an issue for him; he isn’t the one having to clean the litter box after all. However, the parents really aren’t keen on the idea of having one. The only reason they might get one is to make the kids happy. Let’s say if Santa is the one responsible for the gifts, getting the cat has 90% chance, if it’s the parents, only 10%.

Now the calculation. Let’s start from the same starting point as for the cookie incident, so we can compare the two inferences.

The smaller kid’s faith has been further solidified by the appearance of the cat: from 90% it got up to almost 99%! A 9% increase.

The cat was a major win for the Santa story for the big kid as well. His belief shot up from a mediocre 50% to a firm 90%. That’s a 40% increase!

Let’s summarize the results:

As the math demonstrates, our starting point, the prior belief (pₙ), is incredibly powerful. A firm belief, much like my conviction in gravity, is mathematically stubborn. It takes insanely extraordinary evidence to move the needle. However, once doubt creeps in, the same evidence causes much larger swings in belief.

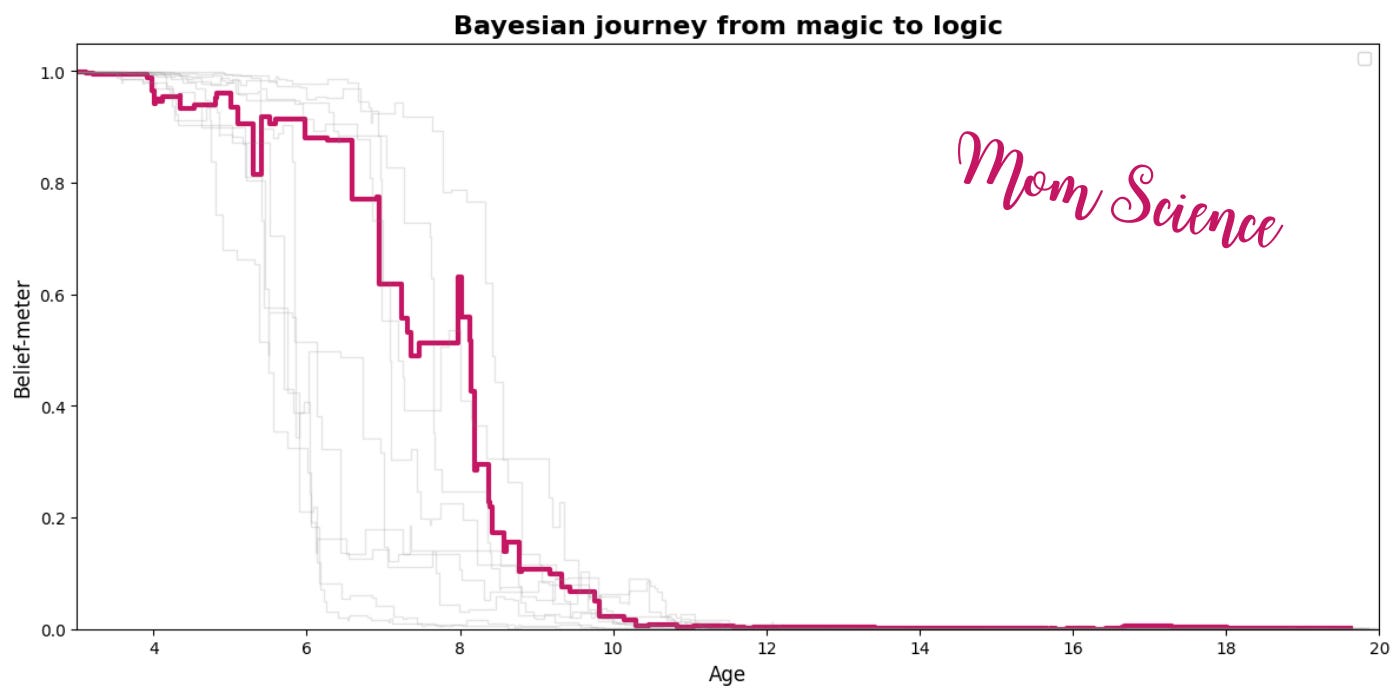

Ultimately, I didn’t stop believing because of one single event. Instead, a series of small cracks in the story slowly shifted my probability of Santa’s existence from a certainty to an impossibility. We don’t just lose our childhood magic; we simply update our variables until the truth becomes the only logical conclusion.

Here’s a little sneak peek at my first attempt at modeling the debunking journey. Stay tuned for the details!

Mills, C. M., Goldstein, T. R., Kanumuru, P., Monroe, A. J., & Quintero, N. B. (2024). Debunking the Santa myth: The process and aftermath of becoming skeptical about Santa. Developmental Psychology, 60(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001662